- Home

- Beryl Kingston

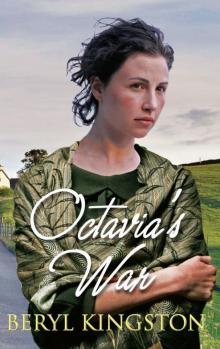

Octavia's War

Octavia's War Read online

Octavia’s War

BERYL KINGSTON

Contents

Title Page

Acknowledgements

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

About the Author

By Beryl Kingston

Copyright

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the generous help that she received from the following people:

Jan Mihell of the Lightbox and the Woking Historical Society; Dorothy Gray, Coleen Moore and Sheila Barrett of Mayfield School, who were all evacuated to Woking; Norman Plastow of the Wimbledon Historical Society, for information on the Wimbledon air raids; the administrators and staff of Nuffield Hospital, Woking; Karen Eastwood, head teacher of The Park School, Woking, and her staff; Rosemary Fost and Bronwen Travis, head of development at St Hilda’s College, Oxford; and finally Elizabeth Garrett and her writer’s retreat ‘Cliff Cottage’.

Chapter One

‘Why is it so dark, Aunty Tavy?’ Barbara said. At five years old she was a sturdy child and curious about everything, so a sudden darkness at six o’clock on a summer evening was something to be wondered at.

‘There’s a storm coming,’ her aunt, Octavia, explained. ‘Look at the sky. Do you see all those grey clouds over there? Well, they’re storm clouds.’

The child persisted, standing by her aunt’s elegant cane chair and squinting up at the sky. The clouds were so very grey as to be almost black and there was something about them that she didn’t like at all. ‘Why aren’t they white?’

‘Because they’re full of rain,’ Octavia said. ‘They’re like big black ponds up in the sky. Presently they’ll make a rumbling noise that we call thunder – I expect you’ve heard that before, haven’t you – and then they’ll spill all the water out and we shall have a storm.’

Barbara’s baby sister, Margaret, was standing beside the chair too. Now she edged a little closer to her aunt and held on to the sleeve of her cardigan, just in case. ‘Shall us get wet?’ she asked.

‘We shall if we stay out here in the garden,’ Octavia told her. ‘But not if we get indoors quickly enough.’

‘Shall us run?’

‘Like greyhounds,’ Octavia said, smiling at the child’s earnest face.

‘What’s a greyhound?’ Barbara wanted to know.

‘Time for us to go,’ their mother said, striding towards them across the lawn. ‘I hope you’re not being troublesome.’

Octavia smiled at her reassuringly, dear Edith, with that thick auburn hair and those clear blue eyes and that oddly endearing anxiety. ‘They’re being intelligent and curious,’ she said, ‘which is exactly as it should be. Ask Pa.’

Her father had been watching the exchange in his quiet way, enjoying the children’s curiosity, thinking, as he always did on such occasions, that Octavia was so easy with children and wishing she could have married Tommy and had children of her own. It would have been so good to have had grandchildren. But there, you can’t have everything in this life and she was a great lady, one of the leaders in the world of education and much admired.

‘They’re no trouble,’ he said to Edith, ‘but Tavy’s right. I think we should be getting in. It’s all very well for you little ones and your Aunt Tavy with her long legs. You can run like greyhounds if it starts to rain but I can’t. I’m more of a tortoise.’ He picked up his stick like the explanation it was and the movement dislodged the newspaper he’d been reading earlier and had set aside on the garden table. It fell on the grass, where it lay untidily, its pages fluttered by a sudden breeze. He watched as they turned, one after the other, until they gave a final flick and settled at the morning’s chilling headline, Storm clouds over Europe. How apposite, he thought, but even as the words came into his mind, the first thunder rumbled overhead and the rain began to fall, spattering the paper with large damp spots.

Within seconds the garden was full of movement: Emmeline puffing towards them across the lawn, moving as fast as she could, given her weight, and unfurling an umbrella as she ran. ‘Quick, Uncle,’ she called to him. ‘Let’s get you indoors. I can’t have you taking a chill.’

Edith grabbed a child in each hand and all three bolted like rabbits, Margaret squealing, ‘Us’ll get wet, Mummy. Us’ll get wet.’

Octavia brought up the rear with the paper and the tea tray, skimming across the lawn with the tea cups rattling and thinking it was just as well the milk jug and the teapot were empty. They tumbled into the drawing room one after the other, dampened, laughing and breathless, and Emmeline took the tray from her cousin’s hands and said she’d be back in a jiffy with some towels. By that time it was raining heavily and so dark that Octavia had to switch on the light as though it was already night time.

‘That’s the trouble with storms,’ Emmeline said, busily towelling Margaret’s short bob. ‘They’re on you before you can breathe. You’ll have to stay here till the worst of it’s over, Edie.’

‘I can’t do that, Mum,’ Edith said. ‘I’ve got to be back for Arthur’s tea and we’re late already.’ Feeding her man was very important to Edith Ames and tonight’s meal was even more important than usual because she had something difficult to tell him and she wanted him to have a good tea inside him before she did it. ‘Don’t worry. We’ve got our umbrellas.’

‘Umbrellas!’ Emmeline snorted, glaring at the window. ‘Oh, for heaven’s sake, Edie, they won’t be any use. It’s coming down like stair rods.’ Both little girls turned their heads at once to see if rain really was like stair rods and were impressed to find that it was. ‘Hold your head still, Maggie, there’s a good girl. You don’t want to catch a cold.’

The instruction was as much a warning to her daughter as her grandchild. But Edith was firm. ‘They won’t catch a cold,’ she said. ‘They’ll run like the wind, won’t you, girls.’

‘You’ll all get drowned,’ Emmeline warned, turning her attention to Barbara. ‘That’s what’ll happen. Never mind running like the wind. Anyway, aren’t you going to stay to see your brother? He’ll be home any minute. You’ll stay to see him, surely to goodness. Ten minutes. I mean, what’s ten minutes?’

‘Enough to make us late,’ Edith said. ‘It’s no good you going on, Mum. I can’t be late for Arthur’s tea. Not even for our Johnnie. You know that.’

Octavia had cleaned her rain-spattered glasses and was drying her own frizzy hair in her vigorous way, listening to them with her usual concentration, turning her towel-hung head to watch their faces as the argument progressed. She was aware that Emmeline was being overprotective of these much-loved grandchildren of hers, that Edith was being too dogged in her determination and that neither would give way to the other. There’s nothing for it, she thought, dabbing at her damp sleeves, I shall have to intervene. As head of the family i

t was her job to try to keep the peace and to suggest whatever compromises she could, just as she calmed tempers and suggested solutions as head of her school. ‘How would it be if you went home in my car?’ she said to Edith. ‘Then you wouldn’t be late and the girls wouldn’t get wet.’

Emmeline relaxed at once, saying, ‘Very sensible,’ but her daughter looked worried.

‘That’s ever so good of you, Aunt,’ Edith said, ‘but what about your dinner party?’

‘I shall be back in plenty of time for that,’ Octavia said, speaking with a confidence she certainly didn’t feel, for preparations for the meal were well under way, the agency cook and the waitress were busy in the kitchen and in less than an hour her guests would arrive.

‘But isn’t it Major Meriton?’ Edith persisted.

‘Major Meriton is a very old friend,’ Octavia told her. ‘I’m sure he won’t mind if I’m a bit late.’ But that wasn’t true either. Now that he was middle-aged and a senior official at the Foreign Office, Tommy Meriton had become a stickler for punctuality. It was sometimes quite hard to remember what a relaxed young man he’d been when they were both young. Relaxed and handsome and easy to be with. What a long time ago it all seemed!

‘I’ll keep him amused if you are late,’ her father said. ‘But I’d cut off quickly, if I were you. Time is getting on.’

‘There you are, you see,’ Octavia said to Edith, handing her damp towel to Emmeline. ‘Everything’s taken care of. I’ll go and get the car out of the garage. Wait in the porch. I’ll drive it to the door.’

It was a cheerful journey to Colliers Wood, even though it was so dark that she had to put the headlights on and the rain was torrential, hitting the roof as loud as sticks on a tin drum and sluicing the windscreen with constant streams of water. Propelled by her private urgency, Octavia drove faster than she should have done, persuading herself that there was no danger because there were very few cars about. When they reached the bottom of Wimbledon Hill there were puddles halfway across the road and she drove through them at speed too, so that the impact made a palpable thud and water rose from her wheels in a dramatic white arc. The girls were thrilled with it, calling out ‘Wheeee!’ at each new impact, and Edith said it was like being in a ship at sea, adding, ‘Not that I’ve ever been at sea, but I can imagine it.’

‘It was always such fun driving with you,’ she said to Octavia as they passed the curved steps of Wimbledon Theatre, dramatic on their corner. ‘Off to the theatre to see the pantomime and going home after Christmas at your place in Hampstead all squashed together in the back seat. We had some good times.’

They bumped across the tramlines, heading for the underground at South Wimbledon. The pavements were crowded with rain-drenched women carrying baskets and shopping bags, bent against the wind and struggling with tugging umbrellas. ‘Soon be home,’ Octavia said. ‘And by the look of it, it’s just as well. This is getting worse. Have you got your brollies?’

‘We shan’t need them,’ Edith said. ‘It’s only a step.’

Which was true enough, for Wycliffe Road was short and narrow with the merest scrap of a front garden between the gates and the houses, so she could reach the door of her maisonette in two strides. It only took a few scrambling seconds for all three of them to run into the house.

Now, Octavia thought, waving to them, I can get back. With a bit of luck and some fast driving she could be home and changed before the Meritons arrived.

But her luck didn’t hold that afternoon. The Silver Cloud was standing in the drive. On the one evening when she could have done with Tommy’s predictable punctuality, he’d decided to come early. Sighing, she garaged her car and let herself into the house. Her guests were in the drawing room being entertained by her father. She could hear Tommy laughing in that throaty way of his and his wife saying something in her soft voice that made him laugh again. And as she hung up her keys on the hall stand, the agency waitress walked out of the kitchen carrying twelve glasses and a dish of peanuts on a tray. The evening had begun. Emmeline must have heard her car and given the signal for the aperitifs to be served. There wasn’t time for her to change. Ah well, she thought, removing her cardigan and tucking it into the hall seat, there’s nothing for it, this blouse will have to do. She tried to pat her hair into some sort of order, failed, straightened her glasses, and took a deep breath. Then she opened the drawing room door and walked in, prepared to be teased or scolded.

Fortunately, Elizabeth Meriton was the first person to turn towards her, elegant as always in an understated evening dress, in powder blue pleated silk, as Octavia was quick to notice; her short hair immaculately waved, her nails and lips painted the same bright colour, and Elizabeth was every inch the diplomat’s wife, smiling warmly and saying exactly the right thing. ‘Tavy, my dear. J-J tells us you’ve been on an errand of mercy. Why does that not surprise me? How good to see you.’

The two women kissed cheeks and then Tommy took Octavia’s hands in his and kissed her too. There was no teasing or scolding, he was too pleased with himself for that. ‘We’ve had such an afternoon,’ he said and looked at her eagerly, waiting for her response. ‘I can’t wait to tell you.’

What’s he been up to? Octavia wondered. It had to be something special. She took a Dubonnet from the proffered tray, thanked the waitress, sipped it, and looked a question at him. ‘Well, tell me then,’ she said.

‘We’ve been buying Lizzie’s uniform,’ he said happily. ‘She’s all kitted out and ready for school and she looks superb, doesn’t she, Elizabeth?’

‘He’s been like a dog with two tails all afternoon,’ Elizabeth said, laughing at him. ‘You’d think there’d never been another eleven-year-old requiring a school uniform in the entire history of education.’

‘Ah, but what an eleven-year-old, my dear, and what a school!’ Tommy said, beaming at Octavia. ‘These were no ordinary purchases.’

Which provoked a murmur of amused agreement, for there wasn’t a soul in the room who didn’t know it had always been his ambition to send his much-loved, only daughter to Octavia’s school. His sons were settled at Dulwich, which was right and proper, but his daughter had to go to Roehampton Secondary School and be educated by the great Octavia Smith.

Watching his ardent face Octavia was remembering the evening when he’d first told her how important it was to him, here, just outside those french windows. ‘There’s a war coming,’ he’d said, ‘and open cities will be bombed.’ How terrible those words had seemed to her then but it had been an accurate prophecy and she knew it now after what had been happening in Abyssinia. ‘London schools will be evacuated,’ he’d said. ‘They are already planning it. I want her to be at your school with you. I want you to look after her.’ She’d laughed at his eagerness, for Lizzie couldn’t have been more than six or seven at the time, and teased him that he’d have to wait till 1936 until she could be enrolled at Roehampton Secondary School. And now it was 1936 and she was enrolled, and what was happening in Europe grew more alarming by the day.

The doorbell was ringing. More guests were arriving. She excused herself from the Meritons and walked across the room to greet them.

In her maisonette in Wycliffe Road, Edith had given her daughters their nightly mug of cocoa and put them to bed. Then she’d set the table and cooked Arthur’s supper all nicely in time for his return. It was liver and bacon and fried onions, which was one of his favourites, and they’d both enjoyed it. Now, he was sitting in his armchair in the kitchen, smoking a cigarette with his legs stretched before him and the lower button of his waistcoat undone to make room for the meal, reading the Evening Standard, happy and satisfied, the difficulties of the day behind him.

‘Good?’ she asked him unnecessarily, as she put the dirty plates in the sink.

‘Smashing,’ he said, looking up from the paper. ‘You done me proud.’

His praise pleased her, as it always did. ‘I do me best.’

‘You’re a giddy marvel how you manage,’ h

e said.

She filled the kettle and set it on the gas stove ready to boil some water for the washing-up, swept the tablecloth, folded it, and put it away in the dresser. Then she sat down at the table again.

‘Thing is,’ she said, ‘I got something to tell you.’

‘Oh yes,’ he said, eyes still on the newspaper.

‘Listen to me, Arthur.’

‘I am,’ he said, still reading.

‘No, really listen. It’s important.’

He set the paper aside. ‘I’m all ears,’ he said, smiling at her.

Now that the moment had come she didn’t know how to begin. She looked round at her nice neat kitchen, at her nice dependable gas cooker that she kept so clean and her nice white sink and the pot full of wooden spoons and kitchen knives, at the pretty flowery wallpaper that Arthur had hung for them and the curtains she’d run up on her Singer and the rag rug she’d made for the hearth, at the mantelpiece clock that he’d given her that Christmas because it looked cheerful. And now she was going to lose it all and the clock was ticking reproach at her, in a leaden inevitable way, clunk, clunk, clunk. ‘Thing is,’ she said again. ‘Thing is, I think I’m expecting. Well not think, actually. I know I am.’

He was so shocked he couldn’t disguise it. ‘Oh blimey, Edie!’ he said. ‘That’s torn it.’ Then he was rescued by disbelief. She couldn’t be. He’d always been so careful. I mean, what’s the good of being careful if it happens anyway? ‘Perhaps you’ve got it wrong,’ he hoped. ‘I mean, people do. Women, I mean.’

Her distress tipped into anger. ‘Women!’ she shouted. ‘It’s got nothing to do with women. This is me. Edie. I don’t get things wrong. If I say I’m expecting, I’m expecting and I ought to know.’ Then her emotions tipped again, propelled by that awful repetition. She put her head in her hands and burst into tears. ‘What are we going to do?’ she wept. ‘We can’t have another baby, Arthur. We simply can’t. We can only just manage as it is without another mouth to feed. We’ll have to leave this house and just when we’ve got it so lovely. Oh, Arthur, I’m at my wit’s end. What are we going to do?’

Everybody's Somebody

Everybody's Somebody Sixpenny Stalls

Sixpenny Stalls Francesca and the Mermaid

Francesca and the Mermaid Avalanche of Daisies

Avalanche of Daisies Tuppenny Times

Tuppenny Times A Time to Love

A Time to Love Octavia's War

Octavia's War Gemma's Journey

Gemma's Journey London Pride

London Pride Gates of Paradise

Gates of Paradise Octavia

Octavia Off the Rails

Off the Rails Maggie's Boy

Maggie's Boy Fourpenny Flyer

Fourpenny Flyer